Pretoria, South Africa, 11 October 1901; the height of the Anglo-Boer War. The Dutch Consul-General in South Africa wrote to the Secretary of State in the Netherlands about a possible spy that was discovered: a Dutch nurse was suspected of slipping classified information to the Boers. The story took a strange turn when the female nurse was discovered to be a man.

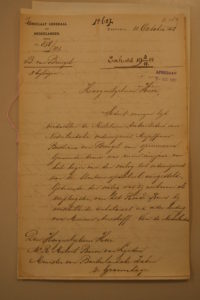

The consul wrote:

For some time the Military Authorities suspected a Dutch teacher, Miss Bastiana van Breugel, of being a spy. Said lady had been appointed more than a year before the war as a teacher at the State Girls’ School. During the war she worked as a nurse for the Red Cross. Earlier this year, she returned to Pretoria from the Boer Lines. Upon her arrival, the Military Authorities thought she was a man in women’s clothes and she was only released after a declaration by her superior, Ms. Ameshoff.

In August Miss Van Breugel became a volunteer nurse in the civilian camp in Potchefstroom, from where she was soon sent back because one of her letters had been blocked by the censors. It contained a description of the block houses along the rail road. During a search of her house, police found a note book with drawings of block houses in Pretoria. Generall Maxwell ordered her to remain in the women’s camp in Pretoria until her departure to the Netherlands.

Because of her warm sympathies towards the Boer Cause, I thought it likely that she tried to help the Boers. After a talk with her, I supported her departure to the Netherlands.

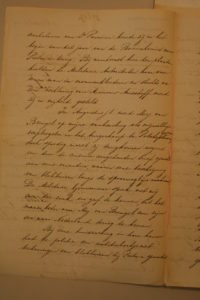

On 5 October I received an urgent call from her and went to the Provost Marshall. He informed me that military doctors had found that Bastiana van Breugel was not a woman, but a not completely developed man. He had me read medical declarations and said that Van Breugel should wear men’s clothes before returning to the Netherlands. Although there were enough reasons to court martial him as a spy, under the extraordinary circumstances, the military authorities did not wish to prosecute. But Van Breugel refused to dress like a man, which could cause great problems.

I pointed out that Van Breugel had been raised as a woman, and had worked as a female teacher and nurse, and asked them to consider having the person dress in their own clothes. But the Provost Marshall considered it against the law to let a man travel in female clothes.

Van Breugel declared to have been raised as a woman, and only discovered around the age of 20 that he was not a woman. On the advice of a doctor, his parents had registered him as a girl with the civil registration. Van Breugel requests to be allowed to return to the Netherlands in his own clothes, to consult with his parents.

I informed the authorities that I was prepared to pay for the stay in Durban and the travel costs to the Netherlands, if Van Breugel would be allowed to leave in his own clothes, so the case could be kept secret for now. Sunday night around 4 AM, Van Breugel departed in men’s clothes to Natal en route to Europe, after his long hair was cut inside the camp.

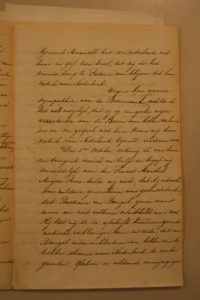

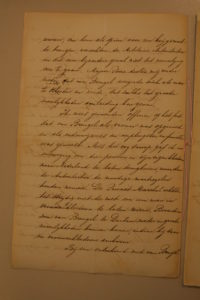

The letter also includes the medical statements regarding the underdeveloped male parts of Bastiana van Breugel. I will not go into the humiliating details here except to say that the doctor established that the male parts were fully functional. If you want to read the whole story, I have included the scans below or in this PDF.

Bastiana van Breugel was born in IJsselmuiden on 18 September 1877. She was a Christian Reformed school teacher. Like many Christian Reformed teachers, she may have read the call by the Transvaal government to ask Dutch teachers to come to Africa. Gold had been found in the Transvaal a decade earlier, and the government used their new-found wealth to hire Dutch teachers to help educate their youth.

Bastiana wrote to the Transvaal Department of Education that she was available for the Transvaal School system, and sent four testimonies of her experience as a teacher. She departed from Southhampton, UK on 12 October 1898 and telegraphed when she arrived in Capetown to hear where she would be stationed. Her father also had plans to come to the Transvaal, to start a brick factory there.

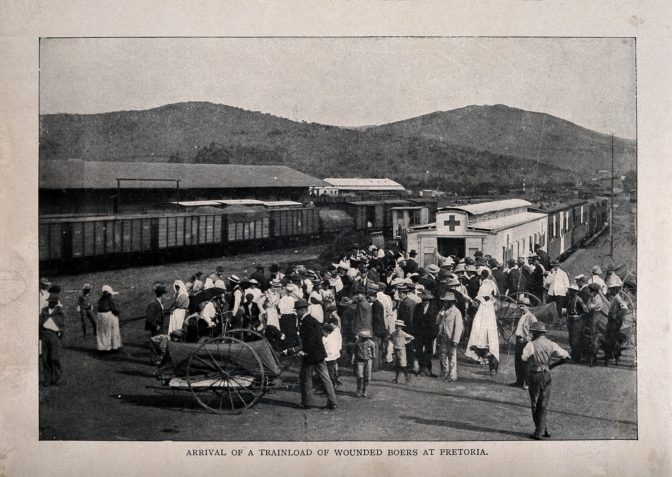

A year after her arrival, the Boer War broke out. The English implemented a scorched earth policy, cutting the Boers off from their supplies by destroying crops. The men were taken as POWs overseas, and the women and children were kept in concentration camps in horrible conditions. The Red Cross did what they could to alleviate their suffering. Bastiana van Breugel was one of the volunteers who joined their forces and helped nurse the sick mothers and children.

Boer War prisoners arriving at the train station. Credits: Wellcome library via Wikimedia Commons (CC-BY)

I stumbled upon the story of Bastiana van Breugel when I was researching my second great-uncle Johan Frederik Kastin. Like Bastiana, he came to the Transvaal to be a teacher, and sympathized with the Boers. He was caught by the English and sent to Madras, India, as a POW. He was one of the people in my Kinship Determination Project that I wrote as part of my portfolio of the Board for Certification of Genealogists. While going through a bundle of papers regarding Boer prisoners in the records of the Dutch Secretary of State, I found the letter regarding Bastiana.

I think her story is a very sad one. The letter says she was 20 when she found out she was a man, which must have been shortly before her departure to South Africa. It is not hard to imagine why making a new start in a different country would appeal to her. It must have been devastating for her when the medical officers discovered her secret, and being forced to wear male clothes while she had been raised as a female her whole life.

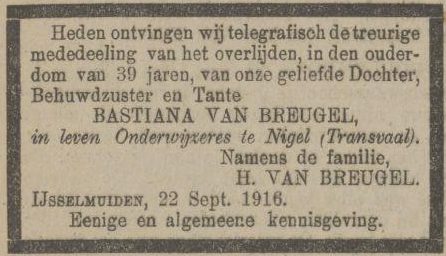

I searched some Dutch indexes to find out what happened to her. On 22 September 1916, her father placed an ad in the newspaper, informing that he had received a telegraph that his beloved daughter, a teacher in Nigel in the Transvaal, had died at the age of 39. I am sorry she died at such a young age, but glad to see that she was able to live out her life as a female teacher in her chosen home land.

Sources

- Secretary of State (Netherlands), file A.189, South-African War 1899-1901, information regarding POWs, file for Bastiana van Breugel; A-files; Department of Secretary of State, Record Group 2.05.03; Nationaal Archief, The Hague, Netherlands.

- “National Archives Repository (Public Records of former Transvaal Province and its predecessors as well as of magistrates and local authorities),” database, National Archives of South Africa (http://www.national.archsrch.gov.za/sm300cv/smws/sm300dl : accessed 2 October 2016), entries for Breugel.

- Death announcement of Bastiana van Breugel, Provinciale Overijsselsche en Zwolsche courant, 23 September 1916, p. 6, col. 1; digital image, Koninklijke Bibliotheek, Delpher (http://resolver.kb.nl/resolve?urn=MMHCO01:000080736:mpeg21:a0022 : accessed 23 September 2016).