This is the twenty-ninth post in a series about my possible line of descent from Eleanor of Aquitaine. In the first post, I explained how I discovered the possible line, and how I am going to verify it one generation at a time. In the last post, I proved that my twenty-fourth great-grandmother Marie of Champagne, countess of Flanders, was the daughter of Marie of France, countess of Champagne.

Biography

Marie of France was born in March or April 1145, the daughter of Louis VII of France and Eleanor of Aquitaine, King and Queen of France and Duke and Duchess of Aquitaine. Her parents’ marriage had been childless for seven years, and Eleanor had pleaded with abbot Bernard of Clairvaux for a child. He said that if Louis VII would make peace with his enemies, the Counts of Champagne, Eleanor would be blessed with a child. Little Marie was born nine months later.

Marie did not grow up with her mother. She was two years old when her parents left to join the Second Crusade (1147-1149). Eleanor came back pregnant after a blessing from the Pope on the return trip, and Marie got a litte sister Alix in 1150. In 1152, the marriage of Louis VII and Eleanor of Aquitaine was annulled, and their daughters remained with their father. Marie probably never met Eleanor of Aquitaine again, though she would later be in touch with her maternal half-siblings through Eleanor’s subsequent marriage to King Henry II of England, including Richard the Lionheart.

Marie’s fate would remain entwined with the Counts of Champagne for the rest of her life. Henry, the eldest son of Louis VII’s former enemy Count Theobald of Champagne, accompanied Louis and Eleanor on crusade. Henry made a favorable impression on the King, and was promised the hand of Louis VII’s daughter Marie in marriage in 1153.

Henry of Champagne and Marie of France met in 1159, though they probably only started living together in 1164. The exact date of their marriage is unknown. After Henry moved the county seat to Troyes, he styled himself Count Palatine of Troyes. As Countess of Champagne and Troyes, Marie was not just Henry’s consort, but also acted as regent when he went on another crusade in 1179-1181. He died shortly after his return. After his death in 1181, Marie served as regent of Champagne during the minority of her son, Henry II. She would take up that role again when Henry II went on crusade.

Marie lived out the rest of her life in Champagne, where she was a patron of the arts. After the death of her son Henry II 1197, she fell into a deep depression. She died in March 1198.1

Marie of France, daughter of Eleanor of Aquitaine

The biographical information above was based on modern publications. To prove the identity of the mother of Marie of France according to the Genealogical Proof Standard, we need to go back to the best possible evidence, using original and contemporary records where available, and do our own analysis.

Patron of the Arts

As countess of Champagne, Marie was a patron of the arts. One of her protégés was the famous poet Chrétien de Troyes, who dedicated his work Erec et Énide to her. A surviving thirteenth-century manuscript of the work includes a portrait of Marie and calls her “ma dame de champagne” [my lady of Champagne].2 This is the only known portrait of Marie of France, countess of Champagne.

Capital P with a portrait of Marie, countess of Champagne

Acts of the Dukes of Normandy

The 1137 marriage of Marie’s parents is documented in several chronicles. A composite manuscript completed in France around 1138-1139 contains a copy of the “Gesta Normannorum Ducum” [Acts of the Dukes of Normandy]. The manuscript is written in different hands, with corrections, which suggests it was written and updated over time. The final entry mentions (abstracted from Latin):

When William, count of Aquitaine, died, his daughter married Louis king of France, his father Louis died in that same year, and Louis succeeded him, making him king of the Franks and Duke of Aquitaine, in the year 1137.3

Gesta Normannorum Ducum, fragment about Eleanor’s marriage to Louis in 1137.

This confirms that Eleanor married Louis in 1137. Since the document was created in 1138-1139, it does not include any information about their children, who had not been born yet.

This last part of the chronicle was created shortly after the marriage, in the abbey of Le Bec in Normandy. Although the monks who wrote the manuscript would not have witnessed the marriage, the marriage of their king would have been known to them.

Life of Saint Bernard

The miracle of Marie’s birth is documented in the hagiography of Saint Bernard of Clairvaux. Bernard of Clairvaux was an influential abbot, whose inspirational speech at Vezelay convinced many people, including Louis VII and Eleanor, to join the Second Crusade. In the medieval period, after somebody was declared a saint, the miracles of their lives were often documented in a vita or hagiography (saint’s life).

Several copies of the vita of Saint Bernard survive. The manuscript below dates from the late 1100s, during Marie and Eleanor’s lifetimes. The Latin text translates to:

The Queen of France, wife of the aforementioned Louis the Younger, had lived with him for many years but had no children. However, there was a holy man who worked with the king to bring about peace, while the queen resisted. When he advised her to abandon her opposition and to suggest better things to the king, during their conversation she began to lament her barrenness, humbly asking him to obtain the blessing of childbirth for her from God. He replied, “If you do as I advise, I will also pray to the Lord for the request you make.” She agreed, and soon peace was achieved. After peace was restored, the aforementioned king—prompted by the queen, who had received the advice—humbly reminded the holy man of his promise. This was fulfilled so quickly that around the same time the following year, the same queen gave birth.4

Life of Saint Bernhard, segment about the miraculous conception, late 1100s.

The manuscript is consistent with the biographical information from modern literature but does not explicitly name either Eleanor or Marie, or the date of these events. The segment just refers to “regina francie” [Queen of France] who gave birth. The description does not even mention if the child was male or female. However, if it had been a boy, that would probably have been mentioned since that would have been a greater miracle that reflected even better on Saint Bernard. The literature references in the literature all trace back to this vita, which seems to be the only contemporary source for Marie’s birth.

Illustrious King Louis, by Abbot Suger

The Illustrious King Louis was started by abbot Suger and continued by others after 1154. Suger was the abbot of Saint Denis, a prominent abbey in Paris that had long had close connections to the kings of France. Abbot Suger was not just the head of the abbey but an important advisor to king Louis VI and his son Louis VII. A manuscript version from the late 1100s survives, created during the Eleanor and Marie’s lives.

In two places, the manuscript mentions Eleanor of Aquitaine as the mother of Marie. It discusses how William of Aquitaine died on pilgrimage to St. James [Santiago de Compostela in Spain], leaving two daughters, “Alenora” and “Aaliz.” The land of Aquitaine went to the oldest, and was given into the hands of king Louis, who married the eldest daughter, Alienora. The second daughter, Aaliz, married Ranulf count of Vermandois. The King had a daughter with Aelinora named Maria.5

The Illustrious King Louis, section about marriage

A few pages later, the manuscript discusses the divorce of Louis VII and Eleanor of Aquitaine. It explains how they were too closely related and the marriage was annulled. Alienor then married Henry, Duke of Normandy, who later became King of England. King Louis was left with the two girls he had with “Aleenoude.” The first, Maria, married Henry count palatine of Troyes. The younger called Aaliz married his brother Theobald count of Blois.6

The Illustrious Louis, section about divorce

This chronicle appears to be a reliable source of information. It was created by Suger, who knew Louis and Eleanor well. Their marriage and divorce took place in 1137 and 1152, during the years that Suger himself was the informant for the information in the manuscript. The surviving manuscript dates from the late 1100s and may well have been copied from the original. Other records, discussed below, verify that there were no significant copy errors.

Later chronicles mention the same information, but most seem to trace back to Suger’s work and do not provide independent verification of the information. Among them was the fourteenth-century Grande Chronique de France, which has an illumination of the council that annulled the marriage between Louis and Eleanor.7

Miniature in Chronicle of France showing the council about the annulment of the marriage

Sigebert and Roberto de Torigni

A monk called Sigebert wrote a chronicle from the time of Abraham until 1112. Sometime before 1150, a monk of the Abbey of Bec, Robert de Torigni, who became abbot of Mont Saint Michel in 1154, acquired Sigebert’s manuscript and kept working on it. He added several facts about Normandy and England, and continued it after the ascension of Henry I to the throne of England. He edited his manuscript several times, and published a first version around 1156/7, a second in 1169 and a third in 1182, 1184, and 1186. The version shown in the first two fragments below was transcribed by the monks at Savigny in the thirteenth century from a copy in the second half of the twelfth century that includes entries from 1114 to 1156. This third fragment was recorded in a continuation of the manuscript after 1156.8

1137: Died Louis sr, king of France, was succeeded by Louis his eldest son, who took as wife the daughter of the duke of Aquitaine, named Eleanor, with whom he had two daughters.9

1137 mention of marriage

1152: As a result of a conflict between Louis, King of the Franks, and his wife, religious persons gathered during Lent at Beaugency. An oath was given before archbishops and bishops that they were related by blood. They were separated by the authority of Christendom. Around Pentecost, Henry, duke of the Normans, count of Anjou, married Eleanor, the Countess of Poitou, whom King Louis had recently divorced due to consanguinity. Hearing of this, King Louis was moved to anger against the same duke, for he had two daughters by her, and thus he did not want her to have sons by anyone else, so that his aforementioned daughters would not be disinherited.10

1152 mention of divorce and second marriage

1164: Henricus, his eldest brother, count of Troyes, took back the daughter of king Louis, whom he had previously sent away.11

1164 mention of marriage of daughter to Henry of Champagne

These are contemporary records, created around the time of these events, though the creator was not an eye witness. However, the information about the king’s marriage, divorce, and his daughter’s marriage would have been known throughout France. The manuscript does not name the king’s daughters, nor does it say which wife gave birth to the daughter that married Henry count of Troyes.

William of Tyre’s History of Deeds Done Beyond the Sea

The chronicler known as William of Tyre was born in Jeruzalem around 1130 and later became the archbishop of Tyre, in present-day Lebanon. In his Historia Rerum in Partibus Transmarinis Gestarum (History of Deeds Done Beyond the Sea), he described the events of the Second Crusade, including a fragment where he described Henry of Champagne as “D[omi]n[u]s Henricus d[omi]ni Theobaldi Senioris comitis filius comes trecenssis eidem d[omi]ni regis gener” [Lord Henry, oldest son of lord Theobaid count of Troyes and the son-in-law of our lord king] in a retelling of events in 1148.12

Henry of Champagne as the king’s son-in-law

William of Tyre wrote this account decades after the Second Crusade, so him calling count Henry the son-in-law of the King of France may have been done with hindsight. However, William of Tyre was careful in other places to refer to people by their correct titles at the time of the events he was writing about, rather than their later titles. This would suggest that Louis VII had already promised his daughter Marie to Henry of Champagne in marriage by 1148.

The oldest version of the manuscript I was able to consult dates from about 1200. The manuscript is not the most reliable source, since it was written decades after the event, and the consulted version may have had copy errors, but it is consistent with the information from literature.

Marie, countess of Champagne, daughter of Louis of France

Other records confirm that Henry, count of Champagne, was married to Marie, daughter of King Louis of France.

In 1159, Henry count palatine of Troyes, donated grain to the abbey at Avenay in honor of “Aeleldis de Marolio magistre comitisse sponse mee” [Adele of Marole, teacher of the countess my spouse].13 The original charter does not survive, but the information was copied into the abbey’s chartulary, their book of charters. The record does not mention Marie by name, but does show that Henry had a spouse by then. This indicates she would have reached the age of 12, the minimum age for girls to consent to marriage, and was born before 1147 (during Louis VII’s marriage to Eleanor of Aquitaine). No evidence suggests that Henry count of Champagne and Troyes was married more than once.

1159 donation

In 1166, Henry of Troyes, count Palatine, supported a grant to the Saint Meddard abbey at Soissons. The grant was made in 1166, during the reign of “Ludovico, Ludovici regis filio, Francorum regnum feliciter moderante, cujus filiam Mariam nomine in conjugio habemam.” [Louis, son of King Louis, the successful ruler of the Kingdom of France, whose daughter named Maria I have in matrimony].14 The original of the charter has been lost, but it was recorded in the cartulary of Saint Meddard that dates from the late 1200s or early 1300s.

Fragment mentioning Marie, daughter of king Louis of France

In 1176, Henry of Champagne issued a charter to renew the privileges of the church of Saint Quiriace in Provins. The charter also includes donations from “nobilis uxoris mee Marie, regis Francorum filie” [my noble wife Marie, daughter of the King of France].15

1176 charter

Detail showing Marie, daughter of the King of France

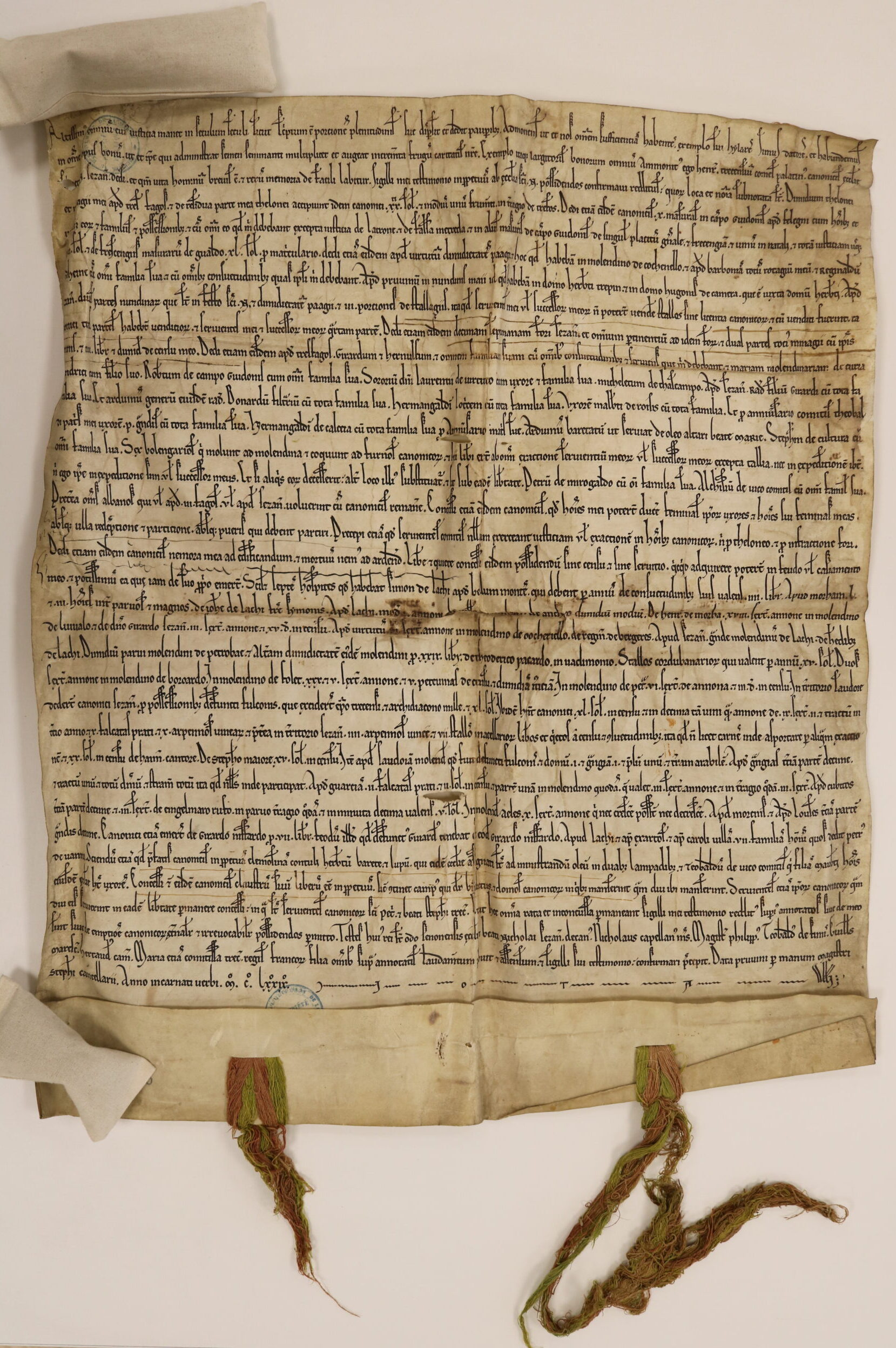

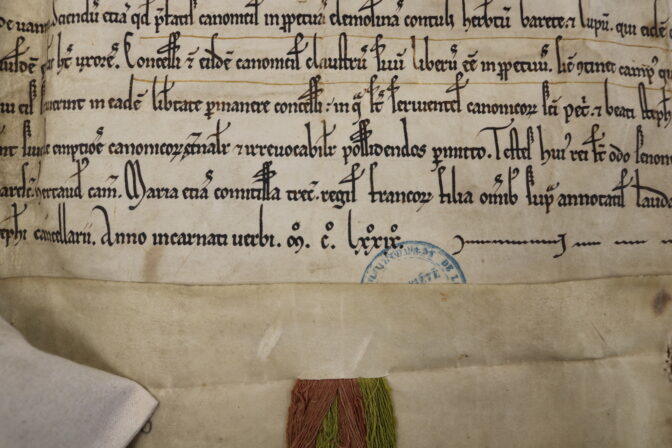

In 1179, “Maria etiam comitissa trec[ensis] regis Francorum filia” [also, Marie, countess of Troyes, daughter of the King of the Franks] witnessed a charter of her husband Henry, whereby he confirmed several possessions and revenues to the St. Nicholas of Sezanne.16

1179 charter. Photo by author

1179 charter, detail

Though the seal of that charter does not survive, it survives on other charters. The text reads “SIGIL . MARIE . REG . FRANCOR . FILIE . TRECENS . COMITISSE” [the seal of Marie the daughter of the king of the Franks countess of Troyes].17 This shows that Marie identified herself as the daughter of the King of France.

Seal of Marie de France, countess of Troyes

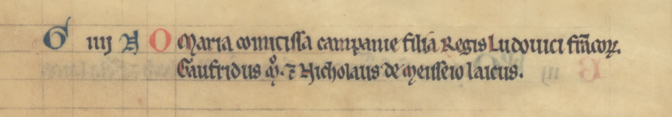

A note about her death confirms her identity as the daughter of Louis of France. “Maria comitissa Campanie filia Regis Ludovici Fra[n]con[iae]” [Marie countess of Champagne daughter of king Louis of the Franks] appears in the obituarium [obituary] of Notre-Dame-aux-Nonnains in Troyes on 4 March, implying that was the date of her death.18 Masses would have been said for her soul. The surviving manuscript dates from 1243-1247 but copied entries from an older version.

Death of Marie in obituary

Eleanor of Aquitaine, wife of King Louis VII of France

Charters confirm that Eleanor of Aquitaine was married to King Louis VII of France from 1137 to 1152, consistent with her being the mother of Marie, born before 1147.

In a charter from 1138, Louis VII called himself (translated from Latin) “Louis, by the grace of god King of the Franks and Duke of Aquitaine.”19 This confirms that he had become the Duke of Aquitaine by that time, consistent with him marrying Eleanor of Aquitaine in 1137.

1138 charter by Louis VII of France

A charter from 1139, that survives in a transcription from circa 1740, confirms that King Louis VII’s wife was Eleanor of Aquitaine. In the charter, she styles herself (translated from Latin) “Helienord [Eleanor] by the Grace of God Queen of the Franks and Duchess of Aquitaine.” She donates mills at La Rochelle to the Templars “for the welfafre of our soul and [those] of our ancestors, and for the welfare ofof the souls of the ancestors of Louis King of the Franks and Duke of Aquitaine our husband.”20

In 1144, “Ludovicus dei gratia rex Francorum et dux Aquitanorum” [Louis by the grace of God King of the Franks and Duke of Aquitaine] issued a charter banning Jews who had converted to Christianity and reverted back to Judaism.21 Again, his use of the title Duke of Aquitaine is consistent with the information from Suger that he acquired the dukedom upon his marriage to Eleanor of Aquitaine, and was still married to Eleanor.

1144 charter by Louis VII of France

In a now lost charter of 27 May 1152, which survives in a transcription from 1740, Eleanor of Aquitaine mentions both her divorce from the King of France and her subsequent marriage to Henry count of Normandy (translated from Latin):

I Eleanor, by the grace of God duchess of Aquitaine and Normandy, make known that … when I was queen with the king of the Franks, the king donated and conceded the forest of Sauria [Sevres?] and appurtenances to the church of Saint Maxent, however the forest was returned to me after I was separated from the king by the judgement of the church. … I again gave Sauria out of my good will … to Saint Maxent. Having been joined with Henry, duke of Normandy and count of Anjoy, … I conceded the concession, the duke agreeing. … The charter was dated at Poitier by the hand of Bernard, my chancellor, in the year one thousand one hundred fifty two since the incarnation of the Lord, on the sixth calend of June [=27 May], Eugenius residing as pope, Louis reigning as king, Geoffrey archbishop of Bordeaux, Gilbert bishop of Poitiers.22

This charter confirms that Eleanor of Aquitaine had divorced Louis VII of France and married Henry Duke of Normandy and Count of Anjou by 27 May 1152. It would be another year before he would become King of England.

In 1158, Louis issued another charter, styling himself “Ludovicus dei gratia rex Francorum” [Louis by the grace of God king of the Franks].23 His omission of the title of Duke of Aquitaine is consistent with him divorcing Eleanor in 1152, which lost him his claim to her ancestral lands.

1158 charter by Louis VII of France.

Conclusion

A combination of evidence proves that Marie of France, countess of Champagne was indeed the daughter of Eleanor of Aquitaine. Several chroniclers, including abbot Suger who advised her father and was well-informed, mentioned the marriage of Louis of France to Eleanor of Aquitaine and the marriage of their eldest daughter Marie to Henry, count of Champagne. Original records created by Marie, Louis, and Eleanor confirm the facts in the chronicles. Marie of France, countess of Champagne, styled herself as the daughter of the king of France in charters and in her seal. Records created by her husband and her clarified that her father was king Louis of France. Married to Henry of Champagne by 1159, Marie must have been born before 1147. The Life of Saint Bernard shows Louis and Eleanor had their first child, probably a daughter, in 1145. Charters issued by Eleanor of Aquitaine and Louis confirm that they married in 1137 and were married until 1152, proving that Marie was born during their marriage.

Eleanor and Marie apparently had no contact after the divorce, which took place when Marie was seven years old. None of the records created by mother or daughter mention the other. However, the body of evidence confirms that Marie was indeed Eleanor’s child. Many pieces of evidence only named Marie’s father, not her mother, but no sources mentioned a different mother. All the evidence is consistent with the conclusion that Marie of France was the daughter of Eleanor of Aquitaine.

That’s 28 generations done, and it’s DONE. I can finally answer the question I asked 7.5 years ago:

Was Eleanor of Aquitaine my ancestor? Yes, she was!

That’s 28 generations down, 0 to go. PHEW.

Sources

- Theodore Evergates, Marie of France: Countess of Champagne, 1145-1198 (Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, United States: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2019).

Other literature I consulted for my research includes Theodore Evergates, Henry the Liberal: Count of Champagne, 1127-1181 (Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, United States: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2016); Theodore Evergates, Aristocratic Women in Medieval France (Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, United States: University of Pennsylvania Press, 1999); Sara Cockerill, Eleanor of Aquitaine: Queen of France and England, Mother of Empires (Stroud, Gloucestershire, United Kingdom: Amberley, 2022); B. Wheeler and John C. Parsons, eds., Eleanor of Aquitaine: Lord and Lady, New Middle Ages Series (New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2016); Ralph V. Turner, Eleanor of Aquitaine: Queen of France, Queen of England (New Haven, Massachusetts, United States: Yale University Press, 2009); June Hall Martin McCash, “Marie de Champagne and Eleanor of Aquitaine: A Relationship Reexamined,” Speculum 54, no. 4 (1979): 698–711, https://doi.org/10.2307/2850324. - Chrétien de Troyes, “Erec et Énide,” manuscript Français 794, 13th century, fol. 27r; Département des Manuscrits, Bibliothèque nationale de France, Paris, France; imaged at Gallica (https://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/btv1b84272526 : accessed 1 May 2021).

- “Gesta Normannorum Ducum,” circa 1138-1139, fol. 31r; ms. BPL 20, University Library Leiden, Leiden, Netherlands; imaged, “Digital Collections,” Leiden University Libraries (http://hdl.handle.net/1887.1/item:1611194 : accessed 12 March 2025).

- “Vita Prima Sancti Bernardi Abbatis,” manuscript, fourth quarter of the 12th century, fol. 99v-100r; call no. MS-B-43, Universitäts- und Landesbibliothek, Düsseldorf, Germany; imaged, “Digital Collections,” Heinrich Heine Universität Düsseldorf (https://digital.ub.uni-duesseldorf.de/ms/content/titleinfo/5168409 : accessed 18 February 2024).

- Suger, “De Glorioso Rege Luduvico Ludovici Filio,” fol. 174v–175r; ms. Latin 12711, late 12th century, Bibliothèque Nationale de France, Paris, France; imaged, “Gallica,” Bibliothèque de France (https://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/btv1b105434376/ : accessed 17 February 2024).

- Suger, “De Glorioso Rege Luduvico Ludovici Filio,” fol. 176r.

- Les Grandes Chroniques de France, revised edition (1332-1350), fol. 325v; Royal MS 16 G VI, British Library, London, UK; imaged as “Digitised Manuscripts,” British Library (http://www.bl.uk/manuscripts/FullDisplay.aspx?ref=Royal_MS_16_G_VI : accessed 29 January 2020). This website has been offline since October 2023 due to a cyber attack.

- Robert de Torigni, Chronique de Robert de Torigni suivie de divers opuscules historiques de cet auteur et de plusieurs religieux de la même abbaye, Le tout publié d’après les manuscrits originaux, ed. Léopold Victor Delisle (Rouen, France: A. Le Brument, 1872), i–vii.

- Roberto de Torigni, “cronographia, id est temporium description, …” chronicle, 1114–1156, 13thth century copy, fol. 128v, entry for death of Louis of France, 1137; ms. Latin 4862, Bibliothèque de France, Paris, France; imaged, Gallica (https://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/btv1b107208615/f260.item.r=%22latin%204862%22 : accessed 14 March 2024).

- Roberto de Torigni, “cronographia, id est temporium description, …” chronicle, 1114–1156, 13thth century copy, fol. 130v, entry for annulment and remarriage of Eleanor; ms. Latin 4862, Bibliothèque de France, Paris, France; imaged, Gallica (https://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/btv1b107208615/f262.item.r=%22latin%204862%22 : accessed 14 March 2024).

- Roberto de Torigni, chronicle, 1114–1182, 13thth century copy, fol. 110r, entry for marriage of Henry of Champagne to daughter of king Louis of France, 1164; ms. Latin 4861, Bibliothèque de France, Paris, France; imaged, Gallica (https://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/btv1b10038703b/f124.item.r=%22Latin%204861%22.zoom : accessed 14 March 2024).

- William of Tyre, “Historia Rerum in Partibus Transmarinis Gestarum,” circa 1200, fol. 157r; ms. Vat.lat.2002, Vatican Library, Vatican City; imaged, Digivatlib (https://digi.vatlib.it/view/MSS_Vat.lat.2002 : accessed 17 September 2024).

- Abbey of St. Pierre of Avenay, chartulary, 13th-14th century, fol. 26r-v, entry for donation in 1159; call no. H (67) 1, Archives départementales de la Marne, Châlons-en-Champagne, France; imaged at “Arca,” digital library, IHRT (https://arca.irht.cnrs.fr/ark:/63955/md45cc08hm7w : accessed 15 February 2024).

- Abbey of Saint Meddard (Soissons), chartulary, 13th-14th century, fol. 16v-17r, Henry of Champagne grant, 1166; manuscript H 477, Archives départementales de l’Aisne, Laon, France; imaged at “Arca,” digital library, IHRT (https://arca.irht.cnrs.fr/ark:/63955/md042r36v608 : accessed 15 February 2024).

- Henry count of Champagne to Saint Quiriace de Province, charter, 1176; manuscript 219, Bibliothèque Municipal, Provins, France; imaged at “Arca,” digital library, IHRT (https://arca.irht.cnrs.fr/ark:/63955/md82k643dt9m : accessed 15 February 2024).

- Henry count palatine of Troyes, charter, donation and revenues to Saint Nicolas de Sézanne, 1179; ms. G 1310, Archives Départementales de la Marne, Chalons-en-Champagne, France. Photo by author.

- Seal of Marie of France countess of Troyes, 1192-1197; imaged at “Collection de sceaux détachés,” Aube en Champagne, Archives Departementales (https://www.archives-aube.fr/recherches/recherche-globale?detail=580797 : accessed 18 February 2024); citing 42 Fi 97 AN, sc/Ch 52-3.

- “Obituarium Ad Usum Monasterii Beatae Mariae Ad Moniales Trecensis,” manuscript, 1243–1247, fol. 7r; ms. Latin 9894, Département des Manuscrits, Bibliothèque nationale de France, Paris, France; imaged, “Gallica,” Bibliothèque nationale de France (https://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/btv1b531882495 : accessed 28 February 2024).

- Louis VII, charter confirming donations to the abbey of St. Victor, 1138; call number AE/II/149, Archives Nationale de France, Paris, France; imaged, “Florilège,” Archives Nationales (http://www2.culture.gouv.fr/documentation/archim/exposition_florilege.htm : accessed 17 September 2024).

- Léonard (“Dom”) Fonteneau, compiler, Mémoires ou Recueil de diplômes, chartes, notices et autres actes authentiques pour servir à l’histoire du Poitou, manuscript, vol. 25, p. 287, transcription of charter by Eleanor of Aquitaine, 1139; Ms 479 Réserve précieuse Tome XXV, Médiathèque François Mitterrand, Poitiers, France; imaged, “Catalogue Patrimoine,” Médiathèque François Mitterrand (https://patrimoine.mediatheques-grandpoitiers.fr/PATRIMOINE/doc/SYRACUSE/4057258/tome-xxv-iere-serie-r-s-dom-fonteneau : accessed 12 March 2025).

- Louis VII, charter against Jews, 1144; call number AE/II/154, Archives Nationale de France, Paris, France; imaged, “Florilège,” Archives Nationales (http://www2.culture.gouv.fr/documentation/archim/exposition_florilege.htm : accessed 17 September 2024).

- Léonard (“Dom”) Fonteneau, compiler, Mémoires ou Recueil de diplômes, chartes, notices et autres actes authentiques pour servir à l’histoire du Poitou, manuscript, vol. 16, p. 21, transcription of charter by Eleanor of Aquitaine, 27 May 1152; Ms 470 Réserve précieuse Tome XVI, Médiathèque François Mitterrand, Poitiers, France; imaged, “Catalogue Patrimoine,” Médiathèque François Mitterrand (https://patrimoine.mediatheques-grandpoitiers.fr/PATRIMOINE/doc/SYRACUSE/4057249/tome-xvi-iere-serie-mai-dom-fonteneau : accessed 12 March 2025).

- Louis VII, charter about the sale of a tithe by Notre Dame d’Yerres to the cannons of Saint Victor of Paris, 1159; call no. AE/II/165, Archives Nationale de France, Paris, France; imaged, “Florilège,” Archives Nationales (http://www2.culture.gouv.fr/documentation/archim/exposition_florilege.htm : accessed 17 September 2024).

Congratulations with this achievement!

Petje af voor je doorzettingsvermogen!

Ga dit onderzoek nog uitgeven in boekvorm?

Groetjes

Irma

Congratulations! This proves all sceptics wrong who don’t believe that genealogical reeearch can reach deep into the Middle Ages.

Gefeliciteerd! Hiermee heb je alle skeptici die niet geloven dat je met genealogisch onderzoek tot diep in de middeleeuwen kunt komen, de mond gesnoerd.

Schitterend werk Yvette.

Heel inspirerend!

Well done Yvette, very inspirational ! I enjoyed your presentation about it yesterday and am encouraged to finally document my own investigation , after approaching it in a somewhat hit or miss manner for years. Getting ready to learn some Latin and brush up on reading skills !

Just saw your talk, which together with your blog posts was very interesting and well presented. Like you, I have a (supposed) lineage to Eleanor of Aquitaine through Marie de Champagne. However there are a few generations around 1400 that are a bit sketchy- I am now inspired to look into this further!

Top!

It has been so interesting and informative to read about each documented generation. A wonderful example of using the Genealogical Proof Standard. Congratulations on your accomplishment.

Wat een studie!! En erg inspirerend! Een genealogische lijn van mij gaat ook tot aan Eleanor Aquitaine. Alleen gaat die van jou middels Guy of Dampierre, count of Flanders (1226–1305), een zoon van haar 2e huwelijk van Margaret, countess of Flanders (1202–1278). Die van mij gaat middels Jan D’Avesnes (1213-1257), zoon van haar 1e huwelijk van Margaret, countess of Flanders (1202–1278). Enfin de 2 zonen kregen een conflict en zo begon Vlaams-Henegouwse Successieoorlog. Ook een bijzonder historische geschiedenis rondom Margaret, countess of Flanders (1202–1278). Ik probeer ook zoveel mogelijke bewijzen te vinden, doch zoals Yvette dat doet…petje af! Ga door met deze vorm van vertellen aan de hand van historische GPS!

Thank you Yvette for a wonderful series of posts. I have no Dutch ancestry but have enjoyed learning about your methods including your genealogy levels template and your application of genealogical proof standards. Just yesterday I found my own potential descent from Eleanor of Aquitaine, via an illegitimate son of King John of England. It is from a line I have researched thoroughly with primary sources to the early 16th century and secondary sources to the 14th century. The earliest generations are on Wikitree, but appear well referenced, so I have the basis for my own research project. I just need to find the time to devote to it. Thanks for the inspiration!

Wow! I had been waiting for this update since binge-reading the rest of the series about a month ago, and it’s so cool to see all your research come to fruition. I loved whenever you were able to use wax seals as part of your evidence—those close-up pictures are some of the coolest historical artifacts I’ve seen. Hopefully one day in my research I’ll be able to trace back far enough to where I can examine them myself.

I have no idea how I missed this post! I’m so glad to see your success. The satisfaction of typing the final three lines must have been immensely satisfying! I doubt you have plans to do so, but if you ever turned this into a book I would be TAKE MY MONEY! 🙂

Congratulations! Prima! Goed gedaan!!