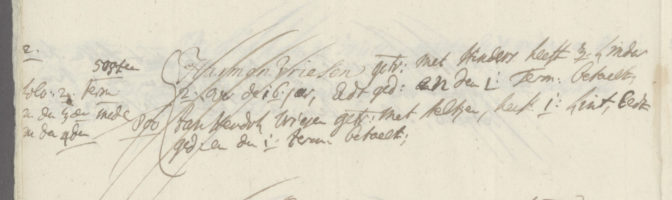

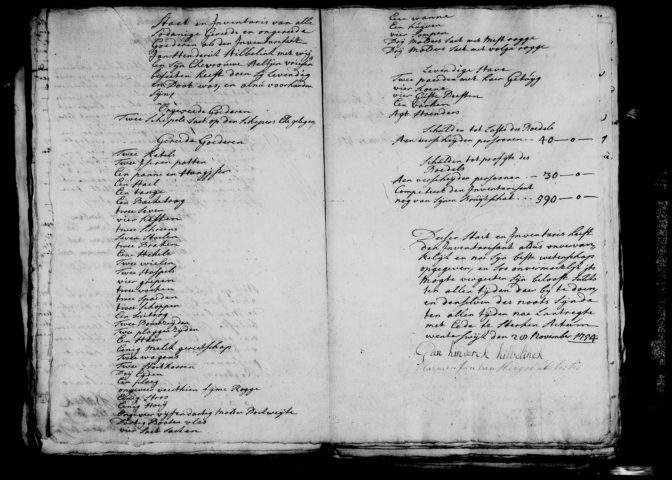

In Winterswijk, Gelderland in 1754, Jan Hendrik Hilbelink was a widower with four young children, who wanted to marry again. Before being allowed to do so, he had to come to an agreement with the guardians of his minor children. He made an estate inventory of all the possessions of him and his late wife, Aaltjen Vriesen. Their children would be entitled to her half.

The inventory consists of the following items:

- 1 piece of farm land

- cooking tools (pots, baking trough, sifs)

- 2 chairs

- farming tools (spades, pitchforks, wheelbarrow, milking tools, plow)

- buckets of buckwheat, flax

- livestock: 2 horses, 8 cows, 1 pig, 8 chickens

- outstanding debts: 40 guilders to misc. unnamed people

- ingoing debts: 30 guilders from misc. unnamed people and 590 guilders in dowry.1

What can we learn from this inventory? What assumptions can we make about the widower and his late wife? How can we test these assumptions?

Analysis of the inventory

The first thing we notice is that Jan Hendrik Hilbelink was probably a small farmer: he owned some farm land, farm tools, and livestock. Most people in Winterswijk were farmers, so that makes sense. But what is most informative about the inventory is what is not there.

The absence of a farm or house tells us that the couple did not own their farm. That was quite common in Winterswijk, where most people were either tenants or serfs. If Jan Hendrik and Aaltjen were serfs, there could have been a heriot [death duties owed to the lord of the manor] listed in the debts to be paid. Since most farmers were tenants, and there is no mention of a heriot, Jan Hendrik and Aaltjen were probably tenant farmers.

Another notable absence is furniture: they only owned two chairs. No table, no bed, no bedding, no cups, no plates, nothing. Neither is there any mention of clothing or jewelry. That tells us that they probably did not have their own household, but lived with someone else who provided everything they needed.

The inventory even gives a clue as to whom they might be living with. The debts owed to the estate include a 590 guilder dowry. This has to be the dowry brought by the deceased wife, since her children would not have been entitled to the new wife’s dowry. 590 guilders was a large sum, especially for a couple with so few possessions. That suggests that Aaltjen’s parents had agreed that she could take over the farm, and that the contents of the farm would be her dowry. The dowry had not been paid yet, despite the fact that Jan Hendrik and Aaltjen had four children so must have been married for a while. This suggests that the parents were still living and had not yet turned over the farm to Jan Hendrik and Aaltjen.

Testing these assumptions

Reading between the lines of the inventory, analyzing what is there and what isn’t, allowed us to form a theory about their circumstances. We think Jan Hendrik Hilbelink and Aaltjen Vriesen were tenant farmers, living with Aaltjen’s parents. Whenever we make assumptions like these, we try to test them using other evidence.

As it happens, there was a special tax levied in 1748, just six years before this inventory: the Liberal Gift. The tax register includes a listing of all the people in the household, so acts like a census.

It shows the following people in one household:

Harmen Vriesen married to Hinders has three children, two over 16 years.

Jan Hendrik Vriesen married to Aeltjen has 1 child.2

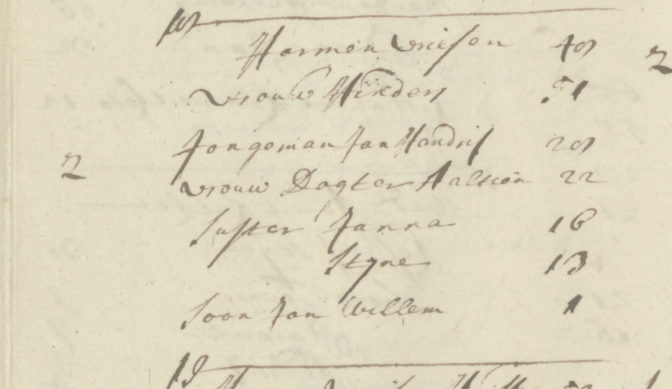

A draft version of this register lists the ages of everyone in the household:

Harmen Vriesen 48

Wife Hinders 51

Young man Jan Hendrik 28

Wife daughter Aaltien 22

Sister Janna 16

[ditto] Stijne 13

Son Jan Willem 1.3

Together, these two versions of the register show that Jan Hendrik married Aaltjen, the daughter of Harmen Vriesen and Hinders, and that the couple lived with her parents. It shows she only had two younger sisters and no brothers, which explains why she was in a position to take over the farm. People in the eastern part of Gelderland and Overijssel used farm names, so Jan Hendrik Hilbelink was called Jan Hendrik Vriesen in the register, after the farm he lived on.

A subsequent inventory from 1767, after the widower died, shows he still lived on the Vriesen farm. By that time, he had received the furniture and other household items and was no longer owed a dowry. His widow agreed that his eldest son from his first marriage would take over the farm. The inventory includes a debt to the Hijink family.4 A 1771 tax record shows that the Hijink family owned the Vriesen farm.5 The debt must have been the rent that was due, showing that the Hilbelink/Vriesen family were indeed tenants, which explains the lack of real estate in the inventories.

Vriezen farm, now a scheduled monument. Credits: Bert van As, Rijksdienst Cultureel Erfgoed (CC-BY-SA)

Sources

- Court of Bredevoort Bredevoort, tuteele en curateele [guardianship records], 1753, 1754, estate settlement of J H Hilbelink; call no. 564, Rechterlijk archief Heerlijkheid Bredevoort [Court Records Bredevoort], record group 3017; Erfgoedcentrum Achterhoek en Liemers, Doetinchem; scans, digital film 007988567, FamilySearch (https://familysearch.org/search/film/007988567?cat=56473 : accessed 2 October 2016).

- Manor of Bredevoort, Liberal Gift 1748, Winterswijk, Woold rot 1, Vriesen; call no. 162, Drost en Geërfden van Bredevoort, Record Group 98; Erfgoedcentrum Achterhoek en Liemers; finding aid and images, Erfgoedcentrum Achterhoek en Liemers (http://www.ecal.nu : accessed 20 March 2015).

- Manor of Bredevoort, Liberal Gift 1748, draft, Winterswijk, Woold rot 1, Vriesen; call no. 158, Drost en Geërfden van Bredevoort, Record Group 98; Erfgoedcentrum Achterhoek en Liemers; finding aid and images, Erfgoedcentrum Achterhoek en Liemers (http://www.ecal.nu : accessed 20 March 2015).

- Court of Bredevoort Bredevoort, tuteele en curateele [guardianship records], 1767, estate settlement of Elisabeth ten Damme; call no. 572, Rechterlijk archief Heerlijkheid Bredevoort [Court Records Bredevoort], record group 3017; Erfgoedcentrum Achterhoek en Liemers, Doetinchem; scans, digital film 007988571, FamilySearch (https://familysearch.org/search/film/007988571 : accessed 2 October 2016).

- District of Zutphen, tax records Winterswijk 1771/1772, “pag. 55,” Vriesen plaatse; call no. 432, Staten van Kwartier Zutphen [States of the Zutphen Quarter], record group 0005; Gelders Archief, Arnhem; finding aid and scans, Gelders Archief (http://www.geldersarchief.nl : accessed 20 March 2015).

A thorough understanding of naming schemes, social classes and inheritance laws is essential for arriving at these conclusions. This differs greatly from my Welsh Quakers I. Pennsylvania at the same time period. Thank you for sharing Yvette.

I love case studies as so much can be learned from them. Thank you for sharing this. You did a great job.