While doing research at the Amsterdam City Archives, I came across a ledger of orphans working for the Dutch East India Company. The register was part of the records of the Burgerweeshuis, the Citizens’ Orphanage.

I was fascinated to read how the orphans would learn a trade like carpentry or sail making, and were able to find employment in one of the most prosperous companies of the era. But while browsing the pages, a more sinister picture presented itself.

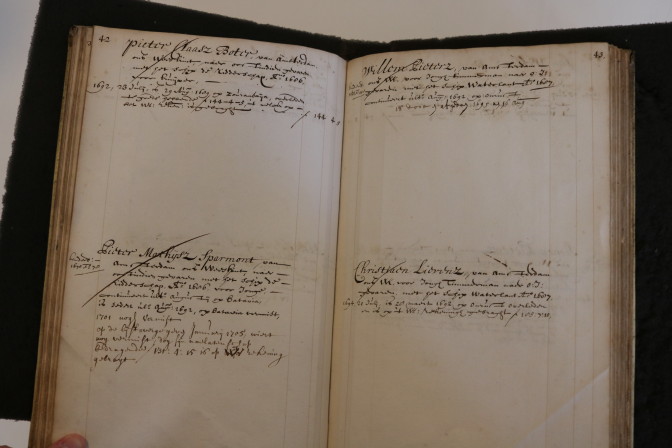

Let’s take a look at a random page from the book and you’ll see what I mean. This page shows how four orphans were employed by the Dutch East India Company:1

- Pieter Claasz Boter from Amsterdam, to the East Indies on the ship de Ridderschap in 1686 as cooper. Died on 29 August 1689 at Zouraubaija [now Surabaya, Indonesia], being owed 144 guilders, 4 “stuivers” [5 cent pieces], 5 pennies, brought into the orphanage’s account on 23 July 1692.

- Pieter Mathijsz Sparmont from Amsterdam went to the East Indies on de Ridderschap in 1686 as a ship’s boy. Missing since the end of August 1692 in Batavia [now Jakarta, Indonesia]. 1701 still missing. In January 1705 still missing, but his estate worth 131 guilders 4 stuiver and 15 pennies brought into the orphanage’s account.

- Willem Pieterz from Amsterdam as young carpenter to East Indies on the Waterlant in 1687. Extended his employment at Onrust [island near Batavia] in August 1692. Is dead and done with 1695 16 August.

- Christiaen Lievenzfrom Amsterdam as young carpenter to the East Indies on the Waterlant in 1687. Died 28 March 1692 at Onrust. 21 July 1694: Brought into the orphanage’s account 185 guilders, 7 stuivers and 10 pennies.

This shows that three of the four children who went to the East Indies died while in the employ of the Dutch East India Company, and one went missing. The orphanage got their back wages, which ran in the hundreds of guilders. To put this in perspective: that would have been enough money to buy a small house.

The island of Onrust near Batavia, 1699. Credits: Unknown painter, Rijksmuseum (Public Domain)

While not all pages are as sad as this, a quick survey showed me that at least one in three, possibly as many as half the orphans who went to work for the Dutch East India Company died within a few years, often resulting in hundreds of guilders flowing back to the coffers of the orphanage.

It seems like the orphanage and the Dutch East India Company made an arrangement that was mutually profitable:

- The orphanage had more children than they could care for. Amsterdam attracted many fortune seekers, many of whom were poor. Housing conditions were appalling and death rates were high, so orphans and abandoned children flooded the orphanages.

- The Dutch East India Company had a big demand for labor. The bad conditions on board and tropical conditions at the trade posts meant that most employees did not last long.

- The orphanage needed money to take care of all the children. If the orphan died, the Dutch East India Company would pay the orphanage the wages that these children earned.

This book does not say what happened to the wages if the orphan survived. I just hope that the orphan would be entitled to their wages at the end of their employment or when they came of age, as a new start in life, but somehow I doubt it.

The whole system feels like a machine: The city churns out orphans, the orphanage gathers them and acts as a holding pattern until they are old enough to work, and the Dutch East India Company uses them as cheap labor until they they die or age out. The ledger demonstrates a sophisticated administration and effective processes, where even the back pay of orphans who died at the other end of the world would find its way back to the Amsterdam orphanage.

Recruiting employees for the Dutch East India Company and the military would have been a very lucrative business for the orphanage. It did not matter whether the children died or not: the orphanage would have one less mouth to feed and would still get hundreds of guilders in back pay.

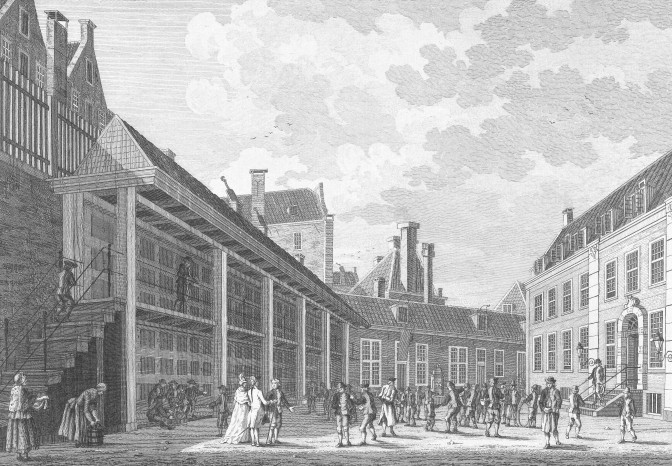

Citizens’ orphanage in Amsterdam. Credits: Cornelis Bogerts, Rijksmuseum (Public Domain)

Although I had read about orphans learning a trade and then working for the Dutch East India Company, I had no idea that so many died and how much money was involved. The scale is staggering: this ledger alone had hundreds of names in it, perhaps even a thousand, and the finding aid shows there were at least ten of these ledgers for different periods, including one ominously described as notes regarding orphans going to war from 1784-1785.

If anyone knows of good literature references regarding this ‘orphan trade,’ please drop me a note in the comments. I would like to learn more about this before jumping to any conclusions based on just one source. I can say that this ledger leaves a bad taste in my mouth because of the low esteem that the administrators of the orphanage seem to have had for the lives of the orphans who were in their care. What do you think?

- Burgerweeshuis [Citizens’ Orphanage] (Amsterdam, the Netherlands), book of orphans who sailed with the Dutch East India Company, 1631-[1731], p. 42-43; Archief van het Burgerweeshuis, Oud Archief [Archive of the Citizens’ Orphanage, Old Archives], record group 367.A; Stadsarchief Amsterdam, Amsterdam.

This seems to be a great find, and a sharp analysis of the process. I would advise to get in touch with several specialists in the field to see what we might be known about this. Indeed, most literature reports orphans being used in colonial (and other) service, but usually in a cover-all manner, not giving much detail. The most interesting part here is the fact that both VOC and Orphanage seem to have calculated in advance on the basis of death rates. For further research one could have a look at the administration and correspondence of both the Orphanage and the VOC, to see if contracts have been kept, outlining the arrangement. This could corroborate the hypothesis, or provide negative evidence, allowing for falsification and an alternative explanation (one would morally hope for).

Some preliminary literature references I found focus either on the positive side (employment for the poor orphans) or on the fact that some orphans were pressed/forced to work for the VOC, but I haven’t yet seen anyone discussing the death rate and the huge sums of money that flowed back to the orphanages as a result. This is not my area of expertise, nor do I intend it to be, so I will just try to find some researchers who do specialize in this field to point it out to them. Analyzing these ledgers could make a great topic for a thesis for a student.

I’ve written an email to a professor in Utrecht who specializes in the VOC and finance in the 17th century, looking forward to hearing if he knows of any related studies or if this would make an interesting topic for a thesis for one of his students.

This strikes a chord with me. My grandfather was orphaned at age 6 and, according to family lore, was taken in by an aunt who owned a tavern where he was put to work. (I haven’t been able to find an aunt who owned a tavern, though.) When, in his early twenties, he emigrated to America, she insisted he compensate her for losing his services, which he did, even after arriving in Chicago. It seems orphans were expected to earn their keep.

Wow, what a sense of family duty on your grandfather’s part. BTW, there were many tavern holders who did not own the taverns they ran. She could have been listed as a “herbergierster” or “cafehoudster” in the population registers though.

My grandfather’s maternal grandfather was listed as herbergier but had died before my grandfather was born. I suppose that’s where the herberg came from..

This is very interesting, but it must be remembered that many sailors also died on these voyages. It was a very dangerous thing to go to sea and especially to the Indies with the VOC. Also many other children also went to sea very young and even in more modern times. My great grandfather Hendrik Simmer (1846 – 1902) went to sea at 9 years old and my grandfather Hendrik Simmer (1888 – 1979) went to sea 13 years old as a coal stoker.

Hi Dave,

But it precisely because it was so dangerous, that I wonder why the regent allowed orphans to let them join the VOC in the first place. Could it be the money that they were making if the orphans did not make it? I’m not suggesting that the mortality rate among orphans was higher than for other employee members, just that the money that the orphanage would receive may have something to do with their willingness to supply orphans for such a dangerous job.

Hi again Yvette:

I certainly can see why you have those suspicions. The VOC did treat native populations badly and some of their business practices were not honorable. The point I was trying to make is that parents also allowed or required their children to go to sea. If that child died and many did, the parents would have also received the child’s wages by the VOC.

Hello Yvette,

My comment has to do with orphans going in the other direction – those being sent by the City of Amsterdam and the Dutch West India Company to New Netherlands. In his book The COLONY OF NEW NETHERLAND A Dutch Settlement in Seventeenth-Century America, Jaap Jacobs discusses the relocation of orphans from Amsterdam to North America. In the chapter 2 [Population and Immigration] he not only discusses the condition of orphans in Amsterdam in the 1600’s, but also details the selection process and the motives of the agencies involved. The references and notes associated with this chapter may be of assistance in indicating the general attitude and practices prevalent at that time.

Hi Yvette,

Roelof van Gelder writes about this fascinating subject in his book: “Naporra’s omweg, Het Leven van een VOC-matroos” ( Naporra’s Detour. The Life of a VOC-sailor) Atlas, Amsterdam 2003, page 216 – 219, and he refers to Groenveld e.a.:”Wezen en Boefjes. Zes eeuwen zorg in wees- en kinderhuizen.(Orphans and Rascals. Six centuries of caring in orphanages and children’s homes),Hilversum 1997.

I was going to make a similar comment to that of M.T. Tinis. My knowledge of the East India Company is limited, but as I have ancestors who came to New Netherlands fairly early (late 1620s), I know more about what happened there. Not only were orphans sent to New Netherland from Amsterdam and other parts of the Netherlands in the 17th c., but they and those who became orphans once there were all under the control of an official in New Amsterdam called the Orphanmaster. Some of these officials attempted to find good guardians or appropriate apprenticeships for the orphans. Others were known to be very corrupt and used the money set aside by the Company for their own use. My own ancestor was 16 when he arrived, as an apprentice. He ended up doing well, and among his five children were leaders in the Colony.

Even into the early 20th c. orphanages in the United States were often dreadful places. Research is now being done into the “Orphan Trains.” Orphanages in big cities in the east coast, especially New York City, were overcrowded. Settlers in the west and Midwest who had few children often lacked servants or farm hands. Orphans in the late 1800s to the early 1910s would be put on Orphan Trains and “hired” when the trains came to small towns. Sometimes these pairings of orphans and families worked out well, with the families actually adopting the children. In other cases, there was much abuse, even leading to death of the children. Few records were kept of what happened to the children when they left the orphanage. At least the Dutch West India Company required records to be kept, such as those you found for the East India Company, so that now the research can be done.

This is my introduction to your blog. Judy G. Russell recommended you today in her blog about the list of genealogists to be voted on. I’m impressed with what I’ve seen today, so signed up. I’ve done some research online into my Dutch ancestors, but can always use more resources.

Hi Yvette, I came to read this article today (was to busy 🙂 ).

Do you have any information on orphans from other provinces working for the VOC or WIC?

Haven’t come across such records yet but I must admit haven’t studied the whole archives also.

Thanks,

Irma

This is fascinating! I have an ancestor who is said to have sailed from Amsterdam to Malacca or Batavia, where he settled and had a family, although there is a record of him having a “orphan debt” with the Malacca Orphan Chamber. Where can I access this record?

I was a ward of the state of The Netherlands from the latter half of WW2 until 1960. I was placed in many orphanages (mainly connected to the Salvos) and also with 4 “foster” homes. These families would use us as virtual slave labour and get rid off me whenever they decided that it didn’t suit them any more (bed wetting, their own kids no longer liked me, etc). I can remember one such occasion clearly, I was transferred from a foster home to a VERY strict institution on the day I turned 11. Nobody said “Happy Birthday” to me on that day, and to this day, 63 years later, it still haunts me! I never remained in one place longer than one year, mostly much shorter. This was a direct result of the way the Dutch Government used untrained staff to take responsibility for a group of kids, like myself. As a result, I cannot accurately remember all the places they put me in. Some, however, I do remember for their brutality. An example: a house for delinquent children called Eikenstein in a place called Zeist. I was sent there after a foster family kicked me out and the Dutch Government could not find a more suitable orphanage for me. In Eikenstein children were not allowed out during the first 4 weeks. The guards routinely hosed us kids down with fire hoses during shower time. A horrible place for a young teenager. Anyway, to cut a long story short, I became mentally affected by my past, and at the suggestion of my GP, I applied to migrate to Australia at the age of 27 (I was married with 2 little kids, aged 1 and 3). I’ve been in Australia ever since. The past, however, will haunt me until I die.

Hi i know you prob wont see this but i have some questions about that orphanage in zeist! i would really appreciate it if u got back to me somehow

Hi Chris, what would you like to know?

Richard

Apologies for leaving a comment so long after the original posting!

… Or rather a question: how young could these orphans be when they went to sea?

These lists didn’t give the ages, but from other records I know that a cabin boy could be as young as ten years old.

Thank you very much.

By happy chance, I have recently found that the skipper on the voyage of het schip Nord Beveland, on which my (documented) ancestor Jonannes Hendrik Hoogewerf sailed east in 1758 with the Middelburg Chamber of the VOC was a notably humane man, whereas some VOC skippers were (of course) absolute brutes, and the VOC was interested above all in results and not in the on-board conditions that produced these. JHH was also married c. 1780 and producing children , and seems to have survived till post 1789, which would seem to argue for a passage out when reasonably young.

JHH most unfortunately did not record his parents’ on signing up. As for In his ancestry, we have an intriguingly divergent pair of possibilities: either (with experience on a hoeker and signing his name up with an ‘X’ he was of Zeeland/ Zuid Holland peasant/fisherman origin OR (a young runaway from an unprosperous branch, and personally stating ‘vlakke,’ = it seems Overvlakkee, as his place of origin) he was (by long family tradition, mutual acceptance, and the documented 1749 birth of a Jan Hoogerwerf, not so far documented as marrying or dying in the Netherlands, who may be our man) from the Rotterdam patriciaat family of Hoogewerff of Poortugaal. This would take us back to the mid C16 – and In the female, Van Driel line to the C14 or even the C12! Great going for an aristocrat, let alone an haute bourgeois. Certainly JHH himself made good in the East becoming a merchant officer (and hence literate) at Tuticorin with the VOC and later, when the VOC fell on hard times, a native officer in the army of the Rajah of neighbouring Travancore, which his son subsequently rose to command, etc. etc..

The story is either one of a rise to prosperity, or a transition from prosperity to prosperity with a decline in between. The Hoogewerff possibility is certainly tantalising … and if unproven, at least still open.

Interesting articles

Hi my ancestor name was JAn van Lochenberg. He was about 16 years old and was an orphan and sailed on the ship called Nephunis on the year 1717 to the cape of good hope south Africa. Can you please help.me find his parents names?

Engeltje Cornelisz van der Bout is my 9th great-grandmother. She was one of the 8 orphan girls from Rotterdam that came on the ship called “China” Trying to find more information on her parents. Hoping you can possibly help. Let me know. Thank you!

Brothers and sisters…

Let’s help orphans and needy people in Indonesia with us

Please support us at ussunnah.org/orphans

Fascinating find. I think that a historian of orphan chambers can contextualize this for you. I have read a book by this scholar that explained the finances and laws associated with orphans:https://history.mit.edu/people/anne-e-c-mccants/

There are other scholars who write in the field, too.