The Dutch war of Independence, commonly known as the Eighty Years’ War or the Revolt, took place from 1568 to 1648. By the mid 1500s, the provinces that would form the Netherlands were part of the Habsburg empire, ruled by king Philip II of Spain. He was a staunch Catholic, while in many places in the Netherlands the Reformation had taken root. The King’s firm oppression of the Reformation led a group of nobles to abjure the King and declare the independence of the Dutch Republic.

During the resulting war, large armies moved across the land, besieging towns and plundering the countryside. As people fought for their faith and freedom, many lives were impacted. Here are five ways that the Eighty-Year-War may have affected our ancestors.

1: They may have been killed

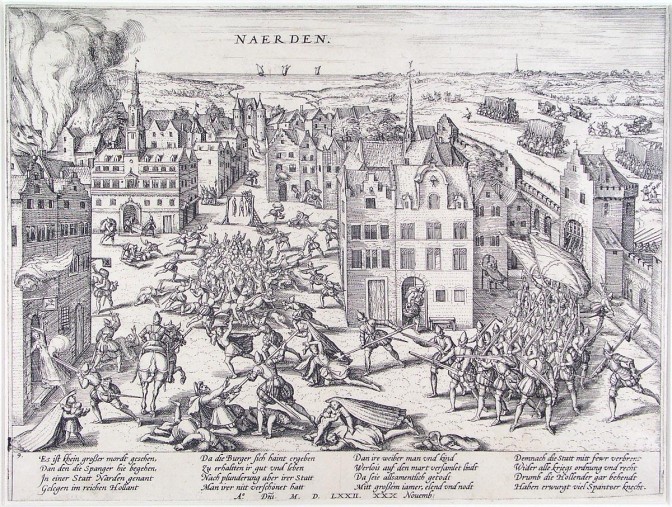

When Spanish troops conquered the city of Naarden in 1572, they did not spare the population. The townsfolk were grouped together and then shot with muskets. The survivors were run through with swords, and the ones who fled into the bell tower were burned alive when the church was set on fire. Citizens who had fled into the fields were caught and strung up on trees, freezing to death. The Duke of Alva, sent to the Netherlands by the Spanish King to squelch the revolt, proudly reported that not one child survived.1

Frans Hoogenberg, massacre of Naarden, 1572. Credits: Wikimedia Commons (Public Domain)

This was not the only time that townsfolk were killed after a siege. Similar bloodbaths took place during the siege of Zutphen (1572), Haarlem (1572-1573), Oudewater (1576) and Maastricht (1576). It was not just the Spanish who did the killing, the Dutch troops killed several martyrs, staunch Catholics who refused to surrender, like the martyrs of Alkmaar (1572), Gorcum (1572) and Roermond (1572). Many more people died in fires that broke out during or after a siege, like in Bredevoort (1606).

Civilians also died in skirmishes with soldiers, like my ancestor Tonis Willinck, whose death was depicted on a 1590s map.

2: They may have been plundered or ransomed

If soldiers did not receive their pay, they went looting. They would roam the countryside, looking for exposed farms and villages where they could steal food or valuables. If they could not find what they were looking for, they would hold people hostage, and demand large ransoms for their release.

This happened to my ancestor Joost Simmelinck from Winterswijk. His family had to borrow so much money to free him that they later went bankrupt as a result.

3: They may have fled

After Antwerp fell to the Spanish in 1585, several protestants fled north, many settling in Amsterdam. They brought knowledge of book printing and cartography with them, leading to a blossoming print industry in Amsterdam.

Map of Amsterdam. Frederik de Wit, 1688. Credits: Wikipedia

4: They may have become soldiers

Both sides of the conflict needed armies. In this period, soldiers were professionals, not conscripts, and soldiers were hired from all over Europe. In my own family tree, I have a Scottish soldier from Edinburgh (Paul Turnbull, known as Paulus Trommel in the Netherlands) and a Swiss soldier from Coer in Punten (Johannes van Gamscher). [I have no idea where Coer in Punten is. If you do, please drop me a line!]. Many of these foreign soldiers stayed after the fighting ended and married local girls.

But it was not just foreign soldiers who moved here. After a town was captured, it would be garrisoned by the conquerors. These garrisons often consisted of a mix of seasoned soldiers who may have come from far away, and local men.

5: It may have affected their religion

As much as we may believe that religion is an individual choice, in reality it is very much shaped by our surroundings. The way were are raised affects our beliefs. It is rare for someone to have a religion for which there is no local place of worship.

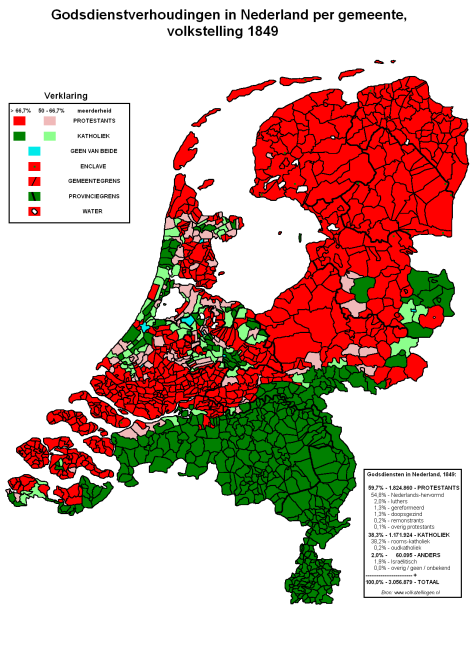

In regions occupied by the Spanish, the Roman Catholic church was the only church allowed. In regions occupied by the Dutch, the Dutch Reformed church was the only church allowed. To this day, this determines the religious landscape in the Netherlands. In the northern and western provinces, that came under Dutch rule early on in the war, the dominant religion is Protestant. In the southern provinces, the dominant religion is Roman Catholic. It can even vary on a local level. For example, in Gelderland, the town of Groenlo was long held by the Spanish while nearby Bredevoort was held by the Dutch. To this day, Groenlo is predominantly Catholic and Bredevoort is predominantly Protestant.

Religion in the Netherlands in 1849. Red = Protestant, green = Catholic. Credits: Dimitri, Wikimedia Commons (CC-BY-SA)

- “Bloedbad van Naarden,” Wikipedia (https://nl.wikipedia.org/wiki/Bloedbad_van_Naarden), version 20 June 2015 12:46.

Coer in Punten, zou dat Chur in Graubünden kunnen zijn?

Ik zou, enigszins afwijkend van Peter Fasol, zeggen: Coer in Punten is de fonetische uitspraak van Graubünden.

Voor mij is Punten Bünden. Het voorvoegsel Grau werd misschien niet begrepen of verstaan als een bijvoeglijk naamwoord dat niet genoteerd hoefde te worden.

Hoe dan ook klinkt Chur als een hele goede kandidaat! Bedankt voor het meedenken. Ik zie een vakantie naar de Alpen in mijn toekomst 🙂

De betreffende voorouder staat op internet met de vermelding “Coer in Punten geallegeert met Switserlant”. Als dit inderdaad in de originele bron staat, lijkt mij dit te slaan op het gehele gebied. Meer uitgebreid luidt de omschiijving van Graubünden namelijk “durch verschiedene Verträge (seit 1497) gleichberechtigter Partner der schweizerischen Eidgenossenschaft”, Chur lijkt mij dus evenzeer in aanmerking te komen als andere plaatsen in Graubünden.

https://de.wikipedia.org/wiki/Kanton_Graub%C3%BCnden :

Der Kanton Graubünden trägt den Namen des ehemals politisch gewichtigsten der Drei Bünde, aus denen er entstanden ist. Der 1367 gegründete Graue Bund (gespaltener Schild, schwarz und silber) wurde 1442 erstmals genannt, vermutlich ein Spottname der Zürcher und Österreicher, der von den Bundsleuten vor 1486 übernommen wurde. Im 15. Jahrhundert erscheint der Name für die sonst Drei Bünde genannte Gesamtheit der Bünde. Im 16. Jahrhundert wurde von Humanisten der Name der römischen Provinz Raetia als Rätien auf das Gebiet der Drei Bünde übertragen.

Die Bünden en de Punten liggen fonetisch dicht bij elkaar. Dat maakt de kansen voor Chur zelfs nog groter.

https://www.gr.ch/DE/institutionen/verwaltung/ekud/afk/sag/dienstleistungen/bestaende/freistaatlichesarchiv/Documents/Urkundensammlung_Teil1_Register.pdf

In het bovenstaande document komt een ‘Johann Luzi Gamser von Chur’ voor met een verwijzingsnummer naar een ander register. Ben er niet in geslaagd daarmee verder te zoeken, helaas.

Oooh, dat is zeer interessant! Hartelijk bedankt!

Inmiddels het bijbehorende regest gevonden in https://www.gr.ch/DE/institutionen/verwaltung/ekud/afk/sag/dienstleistungen/bestaende/freistaatlichesarchiv/Documents/Urkundensammlung_Teil1_ohneReg.pdf

Hieruit blijkt dat deze man in 1730 nog in Zwitserland was, en dus niet mijn voorouder kan zijn die in 1686 in Bredevoort een kind kreeg. Maar de overeenkomst in naam is zo groot dat ik wel een verwantschap verwacht. Een mooie hint!

very interesting, but i still wonder why we sing homage to the spaish king? in the national anthem

That’s how old the song is.

YES they invaded the country and you still pay homage to a invader ?

Who invaded the country? The king of Spain became head of the Habsburg empire by descent. The various parts of what is now the Netherlands became part of the Habsburg empire by marriage alliances over many generations (counts of Gelderland, dukes of Brabant, etc).